Imperial Coronation (2): A Pope Beaten Down

Wikimedia Commons. Photo: Michal Gorski

In the previous article, we discussed the restoration of the Western Roman Empire when Charlemagne was crowned emperor in the year 800 at St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican. We wondered whether his coronation was the result of an impromptu move by the pope, which might have taken Charlemagne by surprise, as he once hinted. To answer this question, we need to examine who the three main players in this story were, and where they came from:

- Pope Leo III

- Empress Irene of the East, who claimed exclusive rights to the imperial title

- And Charlemagne himself, whom we will call “Charles” for now.

Today, we’ll focus on the pope, whose weakness played a decisive role in these events. Unlike his predecessors, Leo III was not of noble birth but came from humble origins. He became pope in December 795, after a career within the Curia’s bureaucracy. From the very start, Rome’s powerful families tried to depose him and replace him with one of their own. Almost immediately after his election, they launched a smear campaign against him, accusing him of immoral and licentious behavior incompatible with the papal office.

Aware of his vulnerable position and limited support, the new pope turned to the Frankish king for protection—the only ruler who could guarantee the Holy See the security that Byzantium had long failed to provide. Whether against barbarian sieges or internal enemies, popes for many years had sought refuge in the West, in the Frankish kingdom, especially since the Carolingian dynasty assumed the crown with Pepin the Short.

At this time, the relationship between Pope Leo III and King Charles was defined by their very different standings: the king was at the height of his prestige, while Leo III desperately needed his support.

One of Leo’s first acts as pope was to win over his protector by sending envoys bearing gifts loaded with symbolism: the keys to St. Peter’s confession and the banner of the city of Rome. By handing over the keys, he was saying, “You are the defender of Peter’s tomb, which makes Rome a holy city; the entire Christian world places its trust in you.” With the city’s banner, he was offering a sign of vassalage, acknowledging King Charles’s lordship over Rome.

In return, Charles sent the pope a generous gift, which Leo used to build a lavish reception hall to properly host the king when he visited the city. Fortunately, a part of this magnificent hall still survives as a precious relic of those times. It is located in the Lateran Basilica, which was then the residence of the popes.

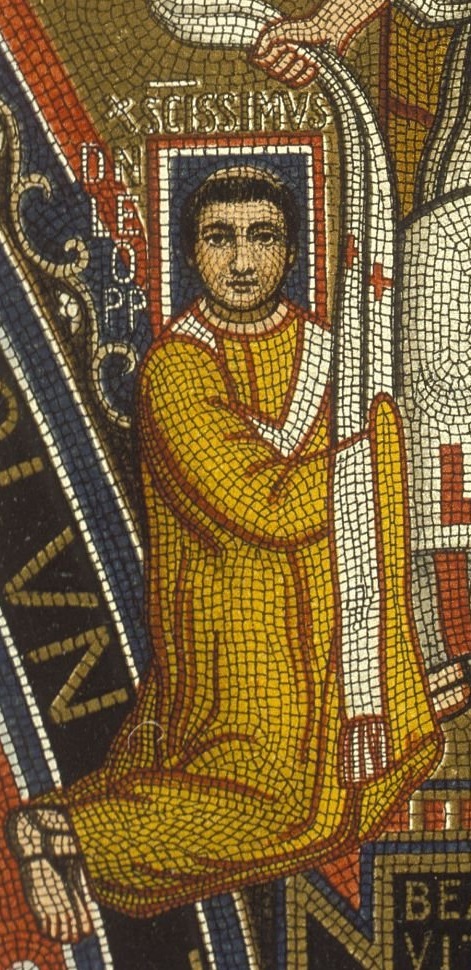

When the papal residence later moved to the Vatican, Pope Sixtus V—a great destroyer of what he considered useless relics—razed over 1,000 years of history by demolishing the Lateran complex. He only spared a few highly symbolic elements, among them the mosaic-adorned apse that presided over Leo III’s grand hall. Today, it is known as the Triclinium Leoninum, or Leo’s triclinium (banquet hall), as it was customary in those days to dine reclined on couches, or tricliniums. The following photograph shows the mosaic that decorates the apse.

The scenes depicted here condense the dominant worldview of that time, as medieval Europe was beginning to take shape. At the center, we see Christ entrusting the apostles with their mission, as the inscription below reads: “Go and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father…”

To the left, the scene recalls the first Christian emperor: Christ himself hands the keys—the symbol of spiritual power—to Pope Sylvester, and the labarum—the symbol of temporal power—to Emperor Constantine.

On the right appear our two main protagonists: Pope Leo III and Charlemagne—King Charles—whom Saint Peter entrusts respectively with the stole (symbolizing spiritual authority) and the banner (symbolizing temporal authority).

This mosaic graphically represents the same idea that the Frankish king had expressed in a letter to the new pope at the start of his pontificate:

“For it is I, with the help of divine Mercy, who must defend the Church of Jesus Christ against the attacks of pagans and the raids of infidels… And you, Most Holy Father, must support the efforts of our armies by lifting your hands to God, just like Moses did, so that through your intercession and God’s grace, the Christian people may always triumph over the enemies of the holy name.”

This was the idea that gave birth to Christendom, a reality coming to life with the restoration of the Roman Empire. The concept was not new—it had been brewing for years, since Charles Martel and Pepin the Short, who had effectively become protectors of the Holy See. Now, it was time to make it official.

In this new worldview, what role remained for the Byzantine emperors—the only legitimate heirs of Constantine? None. They were the great absentees. Their anger at the unfolding events was fully justified, but there was nothing they could do to stop this course. Constantinople was too far from Rome and entangled in its own problems, including the iconoclastic crisis it was enduring. Rome had to turn its gaze toward Europe if it was to survive.

As a curious note, the depiction of Pope Leo III here might actually reflect his real features, although the mosaic underwent heavy restoration in 1743.

Wikimedia Commons

The event that triggered King Charles’s imperial coronation was the assassination attempt on Pope Leo III in the year 799. It was April 25th, the feast day of Saint Mark, when the pope left the Lateran with a small escort to join a procession. Suddenly, he was attacked by a group of men armed with swords and clubs. They beat him mercilessly, trying to gouge out his eyes and cut out his tongue. Though they failed, they left him lying in the street, badly injured and semi-conscious.

He was then taken to a church where the leaders of the conspiracy were gathered, and they beat him again, trying to force him to admit to the accusations against him. The pope stood firm and brave. Eventually, they locked him up in a convent on the Caelian Hill. That very night, his allies managed to sneak in and rescue him by lowering him over the walls to safety outside the city.

Once informed, King Charles took immediate action:

- He invited Leo III to his provisional court in Paderborn, some 1,400 kilometers from Rome. There, the pope was welcomed with a grand ceremony and given the chance to defend himself.

- Charles summoned bishops from across his kingdom to seek their advice on the situation.

- A few months later, the king returned the pope to Rome, accompanied by an impressive delegation of armed men, bishops, counts, and other high-ranking nobles—a true royal entourage.

- Back in Rome, the Frankish delegation arrested the main conspirators and sent them to Frankish lands.

When Charles finally entered Rome in November 800, just a month before the ceremony that would change Europe, the reception he received was far grander than that offered to kings. The pope himself went out to meet him at the city gates, flanked by cardinals, hundreds of priests, and singers chanting psalms.

Officially, Charles’s visit was to resolve the Church’s leadership crisis and try those who had attacked the pope. But behind the scenes, the stage was set for something greater.

At the Vatican, Charles convened an assembly to judge the accused. When the trial ended a month later, the assembly shifted focus: they debated whether to restore the Roman Empire on European soil. On December 23rd, they decided to ask King Charles to accept the imperial dignity.