Imperial Coronation (3): Irene of Athens, the Woman ‘Emperor’

Foto: Robin Foa

The last two entries have been dedicated to analyzing the restoration of the Western Roman Empire, which occurred when the pope crowned Charlemagne emperor in St. Peter’s Basilica on Christmas Day, year 800. After assessing the role played by the weakness of Pope Leo III, we must now turn to another key figure who made this possible: Empress Irene of Athens.

Belonging to a modest Athenian family, the Sarantapechos, nothing suggested that this beautiful and intelligent woman would play a prominent role in history. Her appearance on the scene came in 769 when the Byzantine Emperor Constantine V chose her as the wife for his eldest son, the future Leo IV. Her striking beauty, education, and intelligence were decisive in the “selection process” organized by the emperor to fill the vacancy. The rest was left to fortune: six years later (775), her husband Leo IV ascended the throne, and five years after that he died, leaving his young wife as regent of the Empire while their son Constantine VI, barely nine years old, came of age.

Suddenly elevated to the forefront of politics, to the highest office of the Empire, Irene proved herself capable, skillfully navigating the grave challenges she faced. She showed no hesitation when the Empire was in danger, nor did she lack shrewdness in resolving delicate situations. She escaped conspiracies aiming to overthrow her and successfully completed her regency. For these reasons, she has inspired admiration through the ages, becoming an example of a bold, strong, and intelligent woman.

However, her figure also has a dark and terrible side. Driven by boundless ambition, once she had tasted power, she was unwilling to relinquish it. She obstructed her son’s access to the throne and, ultimately, did not hesitate to stain her hands with the blood of her own flesh and blood: “It is better that one person should die for a people than a people for one person,” she justified. Thus, this newcomer became the first woman since the founding of Rome to assume power in her own name. Never before had a woman sat on the throne of the Roman Empire. On some coins, she even styled herself as “emperor” (basileus, in the masculine), rather than using the feminine form.

But to truly understand Irene of Athens, and, incidentally, to grasp the role she played in the matter at hand—the restoration of the Western Roman Empire—we need to know a little about the context of the era.

* * * * *

First of all, the Byzantine Empire—the continuation of the Roman Empire in its eastern half—was no longer what it had once been.

When the barbarians overthrew the last Western emperor in 476, the eastern part of the Empire remained intact, successfully holding back pressure on its borders. Its domains included Greece and the Balkans up to the Danube frontier, Asia Minor, Syria, and Egypt: a fortunate blend of fertile lands, military strongholds naturally protected by geography, and major trade hubs. Situated between East and West, there was no region more strategically important anywhere in the world.

Emperor Justinian (527–565) even entertained the idea of reconquering the entire western half of the Empire, launching an ambitious plan known as the renovatio imperii—the renewal of the empire. With the invaluable help of General Belisarius, a kind of Cid Campeador of his time (no “vassal” was ever more loyal to his lord, yet none were so poorly rewarded), he reconquered the territories of North Africa—then held by the Vandals—a portion of Hispania, and fought the Ostrogoths until he wrested control of the Italian Peninsula from them.

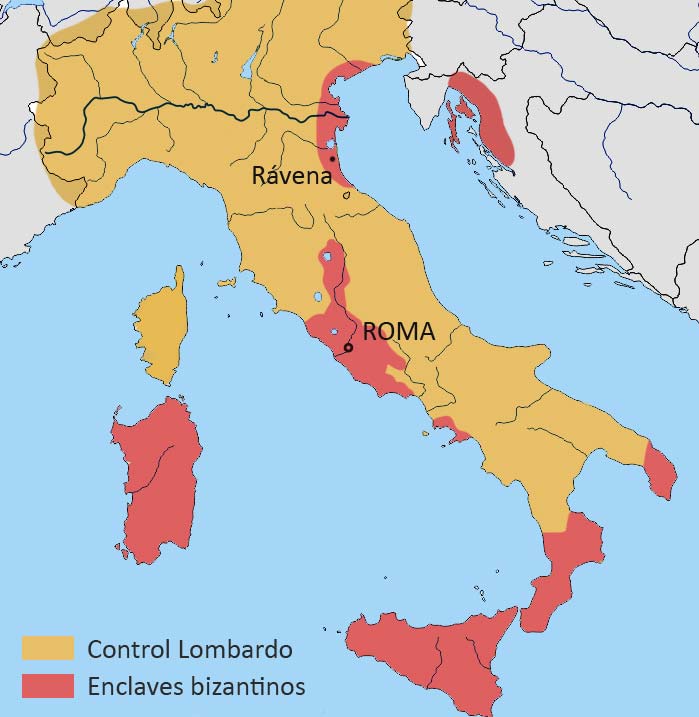

However, the Empire was already expending enormous energy defending its eastern border against the Sasanian Persian Empire and had to keep the Slavs at bay along the Danube frontier. Thus, it couldn’t sustain such a massive effort for long. Italy (except for some enclaves) fell to the Lombards within a few decades, and Hispania was reclaimed by the Visigothic kingdom around 620. The rest of the conquests held out longer—until a new, far more fearsome threat appeared on the horizon: the unstoppable Muslim power.

The following map gives a sense of the scale of this force, which threatened not only Byzantium but the whole of Europe.

Barely two centuries after Justinian, Byzantium had become little more than a survivor. It had lost North Africa, Egypt, and Syria. The Arabs repeatedly raided the lands of Asia Minor, and on two occasions even laid siege to the capital itself (674–678 and 711–718).

If the Empire did not fall, it was only thanks to the incredible strength of Constantinople’s walls and its unbeatable strategic location, which made it nearly impregnable. Alongside these defenses, the Byzantines wielded a secret weapon: the famed “Greek fire,” a mysterious incendiary that the Muslims tried—and failed—to unravel for many years.

The Iconoclast Crisis

By the 8th century, the Byzantine Empire was already stretched to its limits. But as if external threats weren’t enough, a fierce internal conflict erupted: the famous Iconoclast Controversy. Byzantium was a society deeply passionate about theological debates—so much so that even today, the phrase “Byzantine discussions” refers to intense, detailed arguments over subtle points that outsiders may find irrelevant.

In Constantinople, people engaged in these debates with real passion. In earlier centuries, religious councils had sparked massive public turmoil and celebration over the nature of Christ. This time, the hot topic was sacred images—the icons.

The question was: Was it right to depict God, Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the saints in paintings and mosaics? While Jews and Muslims strictly forbade any images of the divine, the Byzantines debated intensely about the appropriateness of such representations. Cultural contact with the Muslim world, with its strict prohibition on divine images, influenced many Byzantine thinkers to see icon veneration as a form of idolatry.

On one side were the Iconoclasts—those who wanted to destroy icons, arguing that worshipping images was outright idolatry, forbidden even in the Old Testament. On the other side were the Iconophiles, who defended icons, saying that people did not worship the images themselves but rather what they represented. For them, images were a bridge from the visible world to the invisible divine reality. They also pointed out that God himself had given humanity an image—Christ, the Word made flesh.

This intense conflict divided the empire for almost a century, in two main phases: from 730 to 787, ended by Empress Irene of Athens herself, and a second wave from 814 to 843.

But the controversy wasn’t just intellectual. There were also political intrigues, power struggles, and personal rivalries behind the scenes.

The emperors, their court, and certain army factions pushed for icon destruction. Meanwhile, the common people, devoted to their icons, and the powerful monastic communities defended them. These monasteries held enormous influence and wealth, which the emperors resented.

The consequences were devastating. Thousands of precious and ancient images were systematically destroyed, unless hidden or smuggled to the West. Monks and laypeople who resisted were imprisoned, tortured, or killed. Many monasteries were dismantled, and centuries of artistic tradition abruptly halted.

Yet, as always happens, the diaspora of artists and monks fleeing persecution spread Byzantine art far and wide: to the Balkans, to the Frankish Kingdom under Charlemagne, and especially to Italy—Rome, southern Italy, and Venice—areas under Byzantine influence where Byzantine mosaics, frescoes, and icons flourished anew. The rich mosaics of Rome’s Santa Práxedes church, near Santa Maria Maggiore, stand as a magnificent testament to this artistic legacy.

Wikimedia Commons. Foto Till Niermann

RELATION WITH ROME

To fully understand the life of Irene of Athens and her influence on Charlemagne’s imperial coronation, we need to briefly look at the complex relationship between Byzantium and the papacy.

When the Western Roman Empire fell in 476 AD, the barbarian Odoacer effectively took control of Italy (476–493). Neither he nor his successor Theodoric, who ruled for a long and prosperous period (493–526), posed serious problems for the pope. At that time, the pope lived in the Lateran Palace (San Giovanni in Laterano), but held little real power.

The greatest threats to Rome arrived shortly afterward, during the reign of Emperor Justinian (527–565). As we’ve seen, Justinian was determined to reclaim the empire’s most sacred lands. His efforts plunged Italy into two decades of devastating wars, severely affecting Rome. The city endured sieges, multiple conquests and reconquests, and even faced the risk of total destruction.

Although Justinian eventually regained control over Italy, his grip remained fragile, limited mainly to key strategic centers such as Rome, Ravenna, and southern Italy. Italy seemed doomed to repeatedly fall into the hands of barbarian kings.

The next rulers to dominate were the Lombards, who invaded in 568. This time, they stayed for two centuries, until the mid-8th century. They never managed to take the Byzantine strongholds of Rome, Ravenna, and southern Italy, but they surrounded them completely.

This patchwork of control, instability, and conflict set the stage for the political tensions that shaped the papacy’s position—and ultimately the moment when the pope crowned Charlemagne emperor, signaling a new era in European history.

Two decades after their arrival, with the Lombards firmly settled in Italian lands, Pope Gregory the Great (590–604) realized that Rome’s future no longer depended on Byzantium, but rather on building understanding with the new rulers of Europe. Some of his predecessors had already experienced tense relations with Constantinople, but Gregory was the one who decisively broke ties with what remained of the Roman Empire. Salvation for Rome was no longer to be expected from the East — a power growing ever more distant, fragmented, and ineffective. Especially since many of these new European rulers, the barbarian peoples, were embracing Christianity.

The rift with Byzantium grew wider and finally exploded in the 8th century during the Iconoclast Crisis. Byzantium, on the verge of being overwhelmed by the Arabs and with dwindling power — incapable of protecting Rome — became embroiled in a dispute that, from the pope’s and the Western perspective, was purely “Byzantine.”

Thus, when around the year 750 the Lombard crisis escalated and the threat to Rome became imminent, the pope did not even consider asking for help from Emperor Constantine V, one of the fiercest iconoclasts, known for destroying images and persecuting monks. Instead, he looked westward to the powerful Frankish kingdom and requested aid from Pepin the Short. The Frankish rulers — or rather, not the kings themselves but their powerful mayors of the palace, the Pippinids — were the true champions of Christendom. They had halted Muslim advances, preventing their penetration into Europe (Charles Martel at Poitiers, 732), and they would defend Rome against the Lombard threat.

We will explore this episode in more detail in another entry. For now, we have painted the backdrop against which the young Irene of Athens enters the scene in 768: first as empress consort, soon as regent, and eventually as the first woman to assume the title of “emperor” in Rome.