What Lies Behind Cosmatesque Art?

Wikimedia Commons. Photo: Vassil

One striking feature that captures the attention of those visiting Rome for the first time is the stunningly beautiful marble floors found in many of its ancient churches. These pavements are crafted from small pieces of ancient Roman marble, arranged in complex patterns that create vibrant, elegant, and eye-catching designs.

A 12th-century Byzantine monk named Philagathos of Cerami was awestruck by the colorful beauty of these floors. He wrote that they resembled “a meadow in springtime, because of the varied colors of the marble forming the mosaic, as if adorned with flowers—except that flowers wither and change color, while this meadow does not wither and is everlasting, for it holds within itself an eternal spring.”

Indeed, these are very old floors, made in the 12th and 13th centuries, before the Avignon Papacy. And in that sense, it’s remarkable that they have survived in such good condition for so long. But the “eternal spring” the monk speaks of has also been sustained through numerous restorations, as we will later see. Today, we’re going to uncover some of the secrets of this art, learn about its creators, and explore the era that made it possible.

First, what stands out is the extraordinary success of this technique, which cleverly reused and recycled the noble materials of ancient Rome. The capital of the former empire certainly had more than enough material to pave every church in the city. And many of them were paved; among those that still preserve their Cosmatesque floors are:

– Saint John Lateran, then the seat of the papacy

– Santa Maria Maggiore

– Saint Paul Outside the Walls

– Santa Croce in Gerusalemme

– San Clemente

– Santa Maria in Aracoeli

– Santa Maria in Trastevere

– Santa Maria in Cosmedin

– San Lorenzo Outside the Walls

– San Giorgio in Velabro

– San Bartolomeo all’Isola

– Santa Pudenziana

– Santa Prassede

– Santi Quattro Coronati

– San Nicola in Carcere

– Santo Stefano Rotondo

– Santa Francesca Romana

– San Benedetto in Piscinula

– San Saba

– San Crisogono (Trastevere)

Many others once had such pavements and have lost them over time—most notably Saint Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican.

But Cosmatesque work wasn’t limited to pavements. This unique mosaic technique was used to decorate many other elements: cloisters, porticoes, tombs, door and window frames, candleholders, tabernacles, pulpits, ciboria (canopies over the main altar), choir screens, presbytery panels, friezes… many of which can still be admired today.

Wikimedia Commons. Fotos: 1. Peter1936F / 2. Sailko / 3. Nicolaseverino / 4. Lalupa

This enormous body of work might suggest the involvement of a vast number of craftsmen. Yet what’s striking is quite the opposite: this monumental achievement was carried out by just a handful of workshops—barely more than half a dozen. We know this thanks to a curious trait shared by these craftsmen: they were proud, confident men, fully aware of the value of their work. For the first time in centuries, a truly Roman technique had emerged—one that connected with the grandeur of antiquity.

These marble workers handled prized materials such as imperial red porphyry, Tunisian yellow marble, verde antico (green marble from Thessaly), and other semi-precious stones from the finest quarries of the ancient empire—now scattered among the ruins of the city and available for reuse. With these, they clothed the churches of Rome in new splendor, helping the city reclaim its role as caput mundi—the capital of the world. Feeling the nobility of their mission, these craftsmen did something rare in their time: they signed their works. These signatures have been the golden thread that scholars have followed to uncover the story of these artists, their workshops, the periods of construction, and even their individual styles. Thus, although still faceless, the medieval marble masters of Rome—known today as the Cosmati—step out of anonymity and offer us a surprisingly vivid image. Let’s meet the creators of these works that continue to dazzle visitors today.

1. MAGISTER PAULUS

The first Cosmatesque master to emerge in history is Magister Paulus, who began working around the year 1100. His name appears on a panel enclosing the presbytery of the cathedral in Ferentino, 70 km southeast of Rome. Based on stylistic similarities, many other works in Roman churches from the pontificate of Paschal II (1099–1118) are attributed to his workshop.

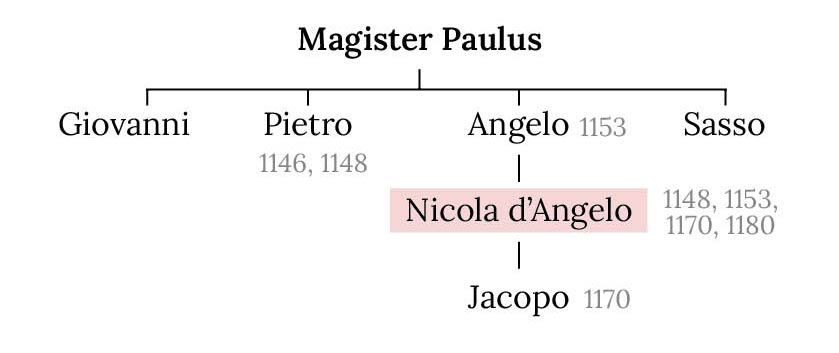

Several family members later joined this original workshop—probably Paulus’s sons or grandsons: Giovanni, Pietro, Angelo, and Sasso. All four signed works attributing themselves to their ancestor and dating from the mid-12th century. A son of Angelo—Nicola d’Angelo—became a prominent artist, architect, and designer. He signed important commissions in Rome and other cities, always within the Patrimonium Sancti Petri, the predecessor of the Papal States, which defined the geographical reach of the Cosmati. Nicola and his own son remained active into the 1270s and 1280s, keeping the family workshop productive for almost a century. This would be the artistic lineage of Magister Paulus:

2. THE WORKSHOP OF LORENZO

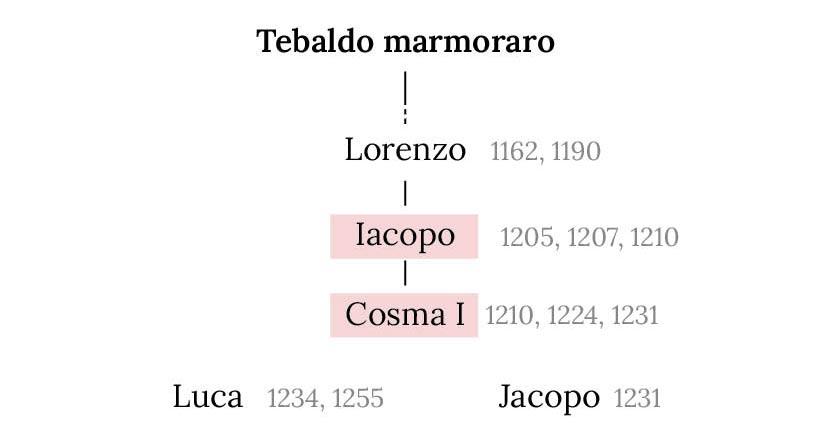

This would become the most prolific of all the Cosmatesque workshops. Its patriarch was the marble worker Tebaldo, a contemporary of Magister Paulus. He worked, like Paulus, from the early 12th century under Pope Paschal II—a great builder who gave a significant boost to the early Cosmatesque artists.

About half a century later, around 1162, one of Tebaldo’s descendants, Lorenzo, began his work. But the workshop only truly flourished two decades later, with the arrival of his son Jacopo, around 1185. This date is considered by scholars the turning point between “pre-Cosmatesque” and fully developed Cosmatesque art.

Jacopo would become the favored architect of Pope Innocent III (1198–1216), widely considered the pinnacle of papal temporal power in the Middle Ages—and the “Cosmatesque pope” par excellence, due to the vast number of commissions he awarded to beautify Rome’s churches.

One of Jacopo’s sons, Cosma, is the reason why these proud Roman marble workers are now known collectively as the Cosmati. In the mid-18th century, when this art form began to be studied systematically, scholars noticed the frequent recurrence of Cosma’s name in inscriptions. They coined the term “Cosmatesque” to describe the style and dubbed its practitioners the Cosmati.

Jacopo and his son Cosma worked during the first third of the 13th century—the golden age of Cosmatesque art. Together, they created the splendid portico of the cathedral of Civita Castellana (50 km north of Rome), proving that the Cosmati were not just mosaicists and marble artisans—they were also true architects and sculptors.

Wikimedia Commons. Foto: Mongolo1984

The last traces of this workshop are found around the middle of the century. After that, all records of the family that gave its name to the “Cosmatesque” art disappear. By then, this type of art was beginning to lose its vitality and was fading away into repetitive formulas. Here is the family tree:

3. VASALLETO FAMILY

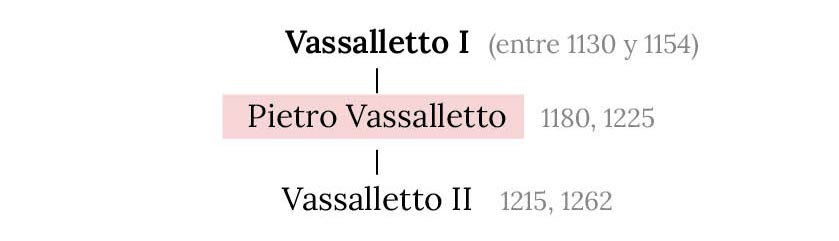

A third important family is the Vassalletto family. Its first known member, whose name remains unknown, appears between 1130 and 1154. However, it was his son, Pietro Vassalletto (active at least since 1180), who signed two true masterpieces that elevated the family to great fame: the cloister of San Paolo fuori le Mura first, and much of the cloister of San Giovanni in Laterano later on. The latter was executed between 1220 and 1230, during the peak of the Cosmatesque style’s splendor.

Wikimedia Commons. Foto: Kuld

Another interesting detail, based on what we know about this family, is that the different workshops could collaborate on certain projects. For example, the magnificent Paschal candleholder of San Paolo fuori le Mura—which was miraculously saved from the fire that devastated the basilica—bears the joint signature of the great Pietro Vassalletto and Nicola d’Angelo, the finest artist from the Paulus workshop.

4. OTHER WORKSHOPS

Only a few other workshops are known to us—among them, that of Pietro Mellini, which also included a Cosma among its members and remained active until the late 13th century, just before the Avignon Papacy. Another was the family of Ranuccio or Rainerio, who did not work in Rome itself, but in nearby towns. A few individual names have also come down to us, such as Drudo de Trivio, Pietro Oderisi, and a Dominican friar.

But overall—as mentioned before—it was just a handful of workshops, barely half a dozen, that carried out this monumental task.

What remains invisible to history, however, is the multitude of artisans who must have worked behind the sixty or so master craftsmen whose names we know—people who spent their lives cutting marble with painstaking precision, from morning until night, year after year, until the end of their days.