A Porphyry Disc in St. Peter’s Basilica

The magnificent marble floor of St. Peter’s Basilica contains, near the entrance, a large red disc that, despite its size, goes unnoticed by many visitors. It is a porphyry disc measuring 2.58 meters in diameter. There is no inscription to hint at its significance, and many people step on it without suspecting its importance. But anyone familiar with the powerful symbolic meaning that red porphyry held in the ancient world might guess that this stone holds a story.

In ancient Rome, red porphyry was an exceptionally valuable material. Throughout the empire, it was only found in a single quarry: Gebel Dokhan, in Egypt. In addition to its unique color and appearance, it was prized for its hardness and durability. For these reasons, its use was strictly reserved for kings and emperors. It became known as “imperial porphyry.”

And indeed, this seemingly unremarkable disc carries a story that spans millennia.

The disc was originally located in the old Basilica of St. Peter, built by Emperor Constantine in the 4th century. Back then, it was not placed where it is today, but rather at the front of the church—where the faithful would kneel to pray before the tomb of Peter. That explains the use of this semi-precious stone, traditionally associated with royal dignity, in a basilica built to honor the memory of the “prince of the apostles.”

When the new floor was laid in the 17th century, preserving this precious relic from the old basilica was an obvious choice. Who would have dared discard a great disc of imperial porphyry linked to the memory of the apostle?

* * * * *

Pero la historia de este disco rojo no termina aquí: en él iban a desarrollarse acontecimientos decisivos para la historia de Europa. Podría decirse, en cierto modo, que sobre esta piedra resurgió el Imperio Romano de Occidente, cuando llevaba muerto más de tres siglos. El acontecimiento tuvo lugar en una fecha precisa: el día de Navidad del año 800. Mientras estaba arrodillado en esta losa, postrado ante la tumba del apóstol, el rey de los francos –Carlos, más conocido como Carlomagno– fue coronado emperador por el papa León III. Esta ceremonia iba a dar un giro crucial a la historia de Occidente.

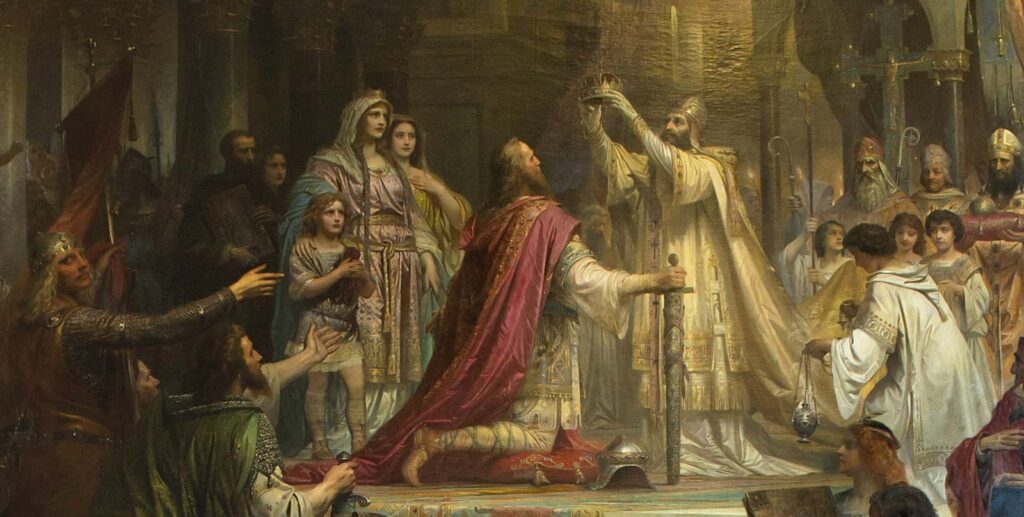

But the story of this red disc does not end here: decisive events for the history of Europe were to unfold upon it. In a way, it could be said that the Western Roman Empire was reborn on this very stone, after having been dead for more than three centuries. This historic moment occurred on a precise date: Christmas Day in the year 800.

While kneeling on this slab, before the tomb of the apostle, the King of the Franks—Charles, better known as Charlemagne—was crowned emperor by Pope Leo III. This ceremony would mark a crucial turning point in the history of the West.**

Since Odoacer deposed the last Roman emperor, Romulus Augustulus, in 476, the Empire had ceased to exist in the West. It would continue for a thousand years in the eastern half, known as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantine Empire, with its capital in Constantinople. Thus, the Byzantine emperors were the sole heirs to the Roman imperial legacy.

The western half had become a land of barbarians. With various invading tribes sowing destruction and fighting among themselves, all traces of the civilization that had once enlightened the world vanished within decades. Among these tribes settling in the former empire’s lands, the most successful were the Franks, who under Clovis came to dominate all of what is now France.

Converted to Christianity around 496, Clovis made the Franks the first Christian kingdom of medieval Europe. The Merovingian kings would rule France for two centuries, but by the late 7th century their decline was unstoppable. Nicknamed the “do-nothing kings,” they became mere puppets in the hands of their mayors of the palace—the true rulers of the kingdom.

Within three generations, these powerful mayors replaced the useless kings and established their own royal dynasty. The most outstanding monarch of this new royal line was undoubtedly Charlemagne, who, due to the vast extent of his domains and the prestige of his power, rivaled the ancient emperors. No one was better prepared than him to take up Rome’s mantle and breathe new life into the Empire in the West.

The new imperial reality that began on Christmas Day in 800 was intrinsically linked to Christianity—and also, in a way, to this very slab—because it was upon it that emperors knelt before a power they recognized as superior: that of the apostle Peter, whose authority had been conferred by Christ himself.

This power was divided into two: spiritual authority entrusted to the pope, and temporal authority to the emperor. Both powers recognized and respected each other… At least for a time, because the struggle between them to determine which should prevail would shape the history of the West.

Thus arose, for the first time, the idea of “Christendom,” and what later—in the time of the Ottonians—would be known as the “Holy Roman Empire.”

This alliance between the pope and the Western emperor, beginning with Charlemagne, would have another profound historical consequence: it would widen the growing rift between East and West until the Great Schism of 1054, which definitively split the two worlds. Byzantium broke with Rome. From then on, each would follow its own path.**

Here is the complete list of the 23 kings who continued to be crowned as emperors by the pope, kneeling before Peter’s tomb upon this disc:

1. Charlemagne (December 24, 800)

2. Lothair I (April 5, 823)

3. Louis II (December 2, 850)

4. Charles the Bald (December 25, 875)

5. Charles III “the Fat” (December 25, 881)

6. Guido, Duke of Spoleto (February 21, 891)

7. Arnulf of Carinthia (895)

8. Louis III “the Blind” (901)

9. Berengar of Friuli (March 24, 915)

10. Otto I “the Great” (February 2, 962)

11. Otto II (December 25, 967)

12. Otto III (May 31, 996)

13. Henry II “the Saint” (February 14, 1014)

14. Conrad II “the Salian” (March 26, 1027)

15. Henry III “the Black” (December 25, 1046)

16. Henry V (April 13, 1111)

17. Frederick I “Barbarossa” (June 18, 1155)

18. Henry VI (April 15, 1191)

19. Otto IV (October 4, 1209)

20. Frederick II (November 22, 1220)

21. Charles IV (April 5, 1355)

22. Sigismund of Luxembourg (May 31, 1433)

23. Frederick III (March 19, 1452)

Years after that Christmas Day that crowned him emperor, Charlemagne made a remark about the ceremony that has puzzled historians ever since. He implied that the coronation took him by surprise and that he was unaware of the pope’s intentions. “Had I known what he was going to do,” he said, “I would never have entered the church.”

Could such a momentous event in European history really have been the result of an impromptu decision? In the next article, we will explore the circumstances surrounding this historic ceremony.